By Maria LaMonaca Wisdom

By Maria LaMonaca Wisdom

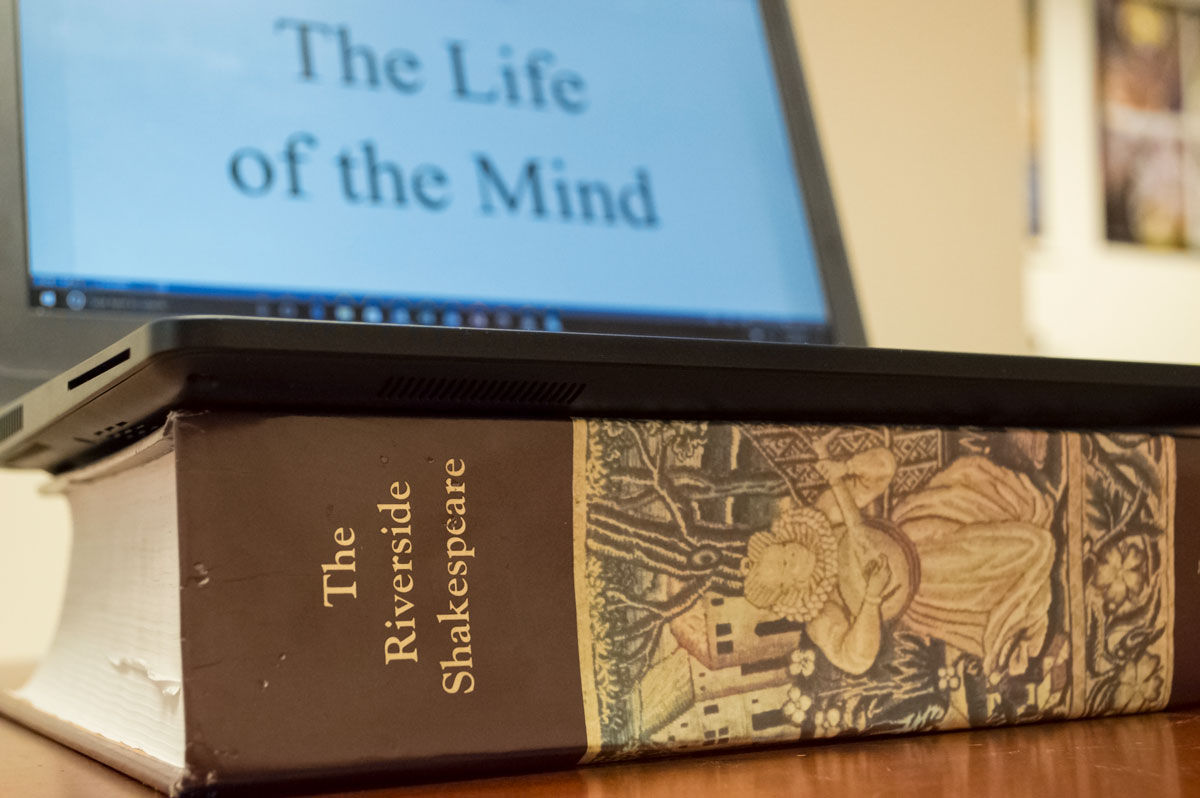

For those of us who shift from faculty roles to nonfaculty administrative appointments, the question of what to do with all the books can be an issue. I still keep Victorian novels in my office. Gone are the early days of my advising role, when I thought I’d pull Middlemarch down from the shelf and use it to provide vocational advice to a student. Yet I feel the need to keep the books around, and my massive Riverside Shakespeare still gets almost monthly use.

I use it to prop up my laptop during videoconference calls.

I feel guilty about this. It feels a little bit like using the Bible as a coaster. And whatever your worldview happens to be, we can probably agree that the Bard was not put on this earth so we could all have an optimal Skype experience.

I bring up the full bookcase and my scholar’s guilt, because it they are both emblematic of a tension that many of us who study, profess, and enjoy the humanities grapple with on a daily basis. How, in the daily grind of professional life, do you clear space for and nurture the “life of the mind”?

At this point you may be thinking that my dilemma is exclusive to those who—by choice or necessity—pursue careers that don’t include teaching or scholarship. That couldn’t, however, be further from the truth. The life of the mind may be more accessible to those who spend their lives as university faculty, but as many professors will tell you, a tenure-track position doesn’t guarantee a blissful, continuous immersion in Big Ideas and Stuff that Matters.

Academics don’t spend much time talking explicitly about the life of the mind, but they have well-formed notions of it, know it when they see it, and can be deeply unhappy when they feel estranged from it.

Perhaps every one of us who shows up in a humanities Ph.D. program had some “imprinting” moment, when we had a transcendent first encounter that kindled in us what we came to recognize as intellectual passion. Perhaps it was first time you discussed a Keats ode in sophomore English class, at (disastrously) the same time someone made you watch Dead Poets Society. Whatever the origin, the intellectual passion may have formed a large part of your motivation to enroll in a humanities Ph.D. program.

Intellectual passion sustains graduate students in many ways. Beyond driving research agendas, it helps students endure the many rigors and privations of a Ph.D. program. But when it comes to mapping out a professional trajectory, sometimes one’s attachment to a scholarly identity and a life of the mind can be a formidable obstacle.

In my advising work with Versatile Humanists at Duke, I encourage even those most dedicated to tenure-track faculty careers to envision multiple professional trajectories. Yet I sense a real fear among at least a few, that pursuing a life outside the academy is tantamount to settling for a diminished existence: a life driven not by intellectual passions, but by prosaic workaday concerns such as making a living, moving up the corporate ladder, or spending one’s days wading through whatever tedious minutiae makes up the typical nonacademic job description.

——- ♦ ——-

Students tend to see faculty at their best, at peak moments of teaching and mentoring. What students often don’t see is how hard faculty—even at many R1 institutions—have to work at cultivating the life of the mind.

——- ♦ ——-

Although I can testify, from firsthand experience, that this need not be the case, you don’t have to take my word for it. To get some sense of the intellectual possibilities inherent in numerous professional trajectories, I recommend that at some point during your graduate studies, you acquire some hands-on nonacademic work experience. Your program of study may not allow you to hold down an internship or paid employment, but remember that in the nonacademic world, volunteering also counts as work experience. If you choose your experiences thoughtfully and well, likely you will not only discover some new talents and competencies, but that you will discover intellectually compelling puzzles and challenges in new arenas.

You should also make a point (even if you see yourself as a future professor) to meet and talk with successful professionals outside the academy. Most of these people are extremely bright, and are deeply engaged in their work. These models may not have been available to us prior to graduate school.

Many students are inspired to go into academia in part because they are caught by the spell of faculty members who are fully immersed in their work, and we might seek to emulate them. Yet remember that students tend to see faculty at their best, at peak moments of teaching and mentoring. What students often don’t see is how hard faculty—even at many R1 institutions—have to work at cultivating the life of the mind. Some struggle to find time to think and write amidst administrative commitments and other obligations conferred by employment at a university.

And there are moments in many scholarly careers—perhaps it’s after the first successful book, or perhaps right after tenure—when faculty have to develop strategies to find new sustainable projects, remain excited about their research, or identify other ways to challenge themselves intellectually and keep growing.

In the coming months, VH@Duke will be reaching out to Duke humanities Ph.D. alumni who are working in a wide range of professional positions beyond the academy. We hope that this initial outreach will lead to networking and mentoring engagements for Ph.D. students. I can’t predict what these conversations will be like for students, but I suspect you may come away realizing that many roads can lead to an intellectually rich and fulfilling life. And that no road—even those that traverse academia—is perfect.