By Aria Chernik and Matthew Rascoff

The official title of our Duke Summer Doctoral Academy course last month was “Ed Tech,” but the main theme of the weeklong workshop was not technology. In fact it was an idea rarely associated with tech – but essential to education: empathy.

Empathy is the heart of good design. Some view design as a primarily visual process, but visual clarity, though essential, comes at the end of a process. Designers begin by understanding their users in order to gather, synthesize, and prioritize their needs and ensure whatever they create actually meets those needs.

What does all this have to do with graduate education? No one asked directly on the first day of our workshop, but the question was on many blinking faces as we began. Our students came from disparate disciplines, ranging from religion to engineering to biomedical science. They were at different stages in their doctoral studies. Few had experience with design.

We had five days to show why design thinking matters for them.

A Sprint and “A Breath of Fresh Air”

The Doctoral Academy is a new initiative for Duke Ph.D. students, offering summer short courses that provide an intensive introduction to important topics not typically included in a doctoral curriculum. For our course, we modified a five-day design sprint and added constructive critical foundations to address both the practical applications and theoretical implications of ed tech. Our workshop emphasized collaboration, divergent and convergent thinking, iteration, and communication across audiences and media.

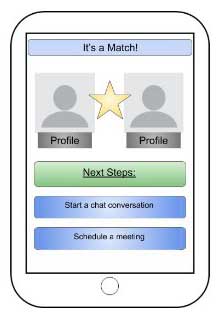

On the first day we organized the students into two teams. The first team tackled the need of first-generation Duke undergraduates to match with mentors who can help them navigate their undergraduate experience and develop skills for professional success. By day four the team had built, tested, and iterated a prototype that connected students with one another and with alumni and ensured a productive and streamlined matching and meeting experience.

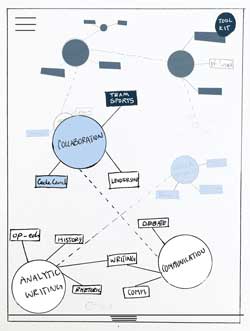

The second team focused on students’ frustration when they do not see a connection between what they already know, what they can learn, and how they can take advantage of Duke’s learning opportunities. The team’s prototype included a “mind map” to make it easier for students to make these connections.

By day five, the two teams “pitched” their products and received feedback from a panel of expert leaders, including Tracy Futhey, chief information officer at Duke; Mark Samberg, technology innovations manager at the NC State Friday Institute; Maria LaMonaca Wisdom, director of graduate student advising and engagement for the humanities at Duke; and Lucy Kosturko, curriculum specialist and research scientist at SAS.

“This class was such a breath of fresh air in terms of the opportunities for collaboration, technical skills, and fun,” one student wrote. “The breadth of students’ disciplinary backgrounds created an exciting interdisciplinary workspace….”

Empathy and Ed Tech

So what, in the end, does design have to do with graduate education?

The empathetic design process by which the best tech is made has a lot to offer those involved in education. Users and their needs are paramount. If a product or service does not work for them, it won’t (and shouldn’t) succeed in the market.

In education, empathy opens up a process that allows designers and educators to understand and address the needs of learners. Educators do not merely provide content—they design learning experiences. Reconceiving education as learning-experience design can be liberating for instructors faced with the many challenges that come with teaching: achievement gaps, unequal preparation, and other inequities. Design provides a learner-centered problem-solving methodology for turning challenges into solutions.

Digital technologies can be an instrument of problem-solving but they must be rooted in a design process that ensures that what is built is the right thing. This is all the more true of education technology, where educators have extra responsibilities for learners.

There is a fundamental asymmetry in ed tech. Educators are the decision-makers about what gets used in courses but students are the ones who use what faculty select. In the language of economics, that mismatch is a principal-agent problem.

To overcome this mismatch, everyone in the academy should be acquainted with education technology and the design methods by which it is created.

To overcome this mismatch, everyone in the academy should be acquainted with education technology and the design methods by which it is created.

Faculty should make learner-centered ed tech choices for their courses and allow students’ voices to be heard in decision-making. We should make those choices on the basis of what works for students, recognizing that all ed tech embeds a pedagogy.

Future faculty – today’s graduate students – will likely rely on ed tech even more in their teaching. And Ph.D graduates who pursue careers outside academia may build ed tech or even found ed tech startups. Those startups, and the products they build, can distill learning experiences, draw on wellsprings of knowledge, and share the benefits of Duke education.

If you are interested in learning more about design thinking and the transformation of teaching and learning, please visit the Learning Innovation and OSPRI websites, attend one of our events, or engage with us on social media.

We would like to thank Jennifer Francis, Executive Vice Provost for Academic Affairs, who spearheaded the development of the Doctoral Academy and invited us to teach in it; and Carolyn Mackman, Manager of Special Projects in the Provost’s Office, who coordinated the planning.

— Aria Chernik is Lecturing Fellow in the Social Science Research Institute and Director of Open Source Pedagogy, Research + Innovation (OSPRI). Matthew Rascoff leads the Learning Innovation team and serves as Associate Vice Provost for Digital Education and Innovation.